The Forgotten Silk Orchard of Maison Chenal: Echoes of Sericulture in Colonial Louisiana

In the quiet bends of Bayou Chenal in Pointe Coupée Parish, Louisiana, stands a testament to the region's layered past: the sprawling 75-acre estate known as Maison Chenal. Located in the old town of Chenal, Louisiana, this preserved Creole enclave—complete with raised cottages, outbuildings, and manicured parterres—whispers stories of French colonial ambition. But beneath the ancient oaks and pieux fences lie the weathered stubs of massive white mulberry (Morus alba) trees, remnants of an 18th-century orchard that once fueled dreams of a silken empire in the New World. Dating back to the early 1700s, these trees were not planted for their fleeting, perishable fruit but for a far more luxurious purpose: the cultivation of silkworms for silk production, or sericulture. This overlooked chapter in Louisiana's history reveals how European aspirations clashed with the realities of frontier life, even as they imported the ancient Asian craft of sericulture—a traditional agricultural practice that promised refinement amid the subtropical wilds—leaving behind arboreal ghosts that endure today.

A Colonial Cash Crop: The Allure of Silk in New France

The story begins in the humid lowlands of French Louisiana, where the Mississippi's tributaries carved out fertile concessions for settlers. By the 1730s, as France sought to bolster its colonial economy amid rivalries with Britain and Spain, silk emerged as a prized commodity. Native to China, the domestic silkworm (Bombyx mori) feeds exclusively on the leaves of the white mulberry tree—a fast-growing species imported from Asia for its tender, nutrient-rich foliage. One mature tree could sustain hundreds of larvae, which, after gorging on leaves, spin cocoons of fine silk thread prized for textiles, embroidery, and ecclesiastical vestments.

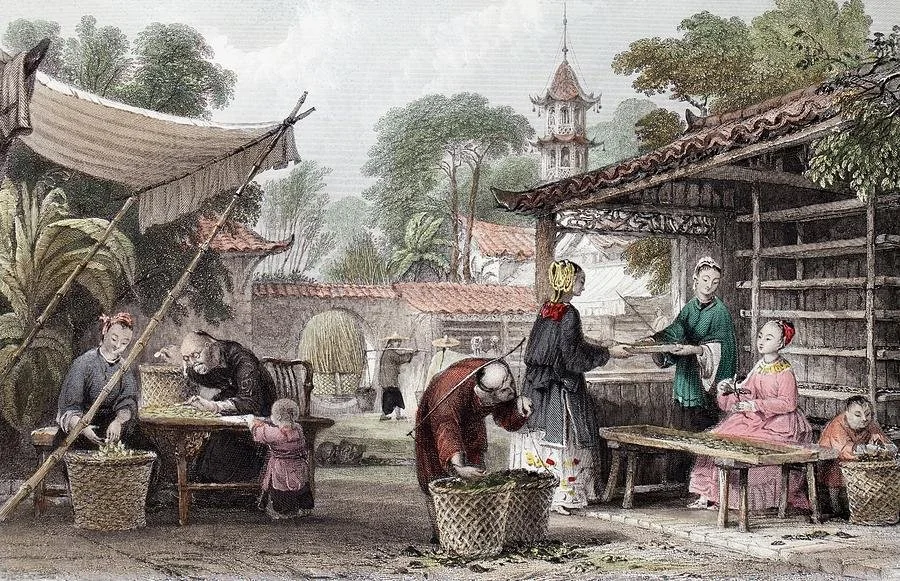

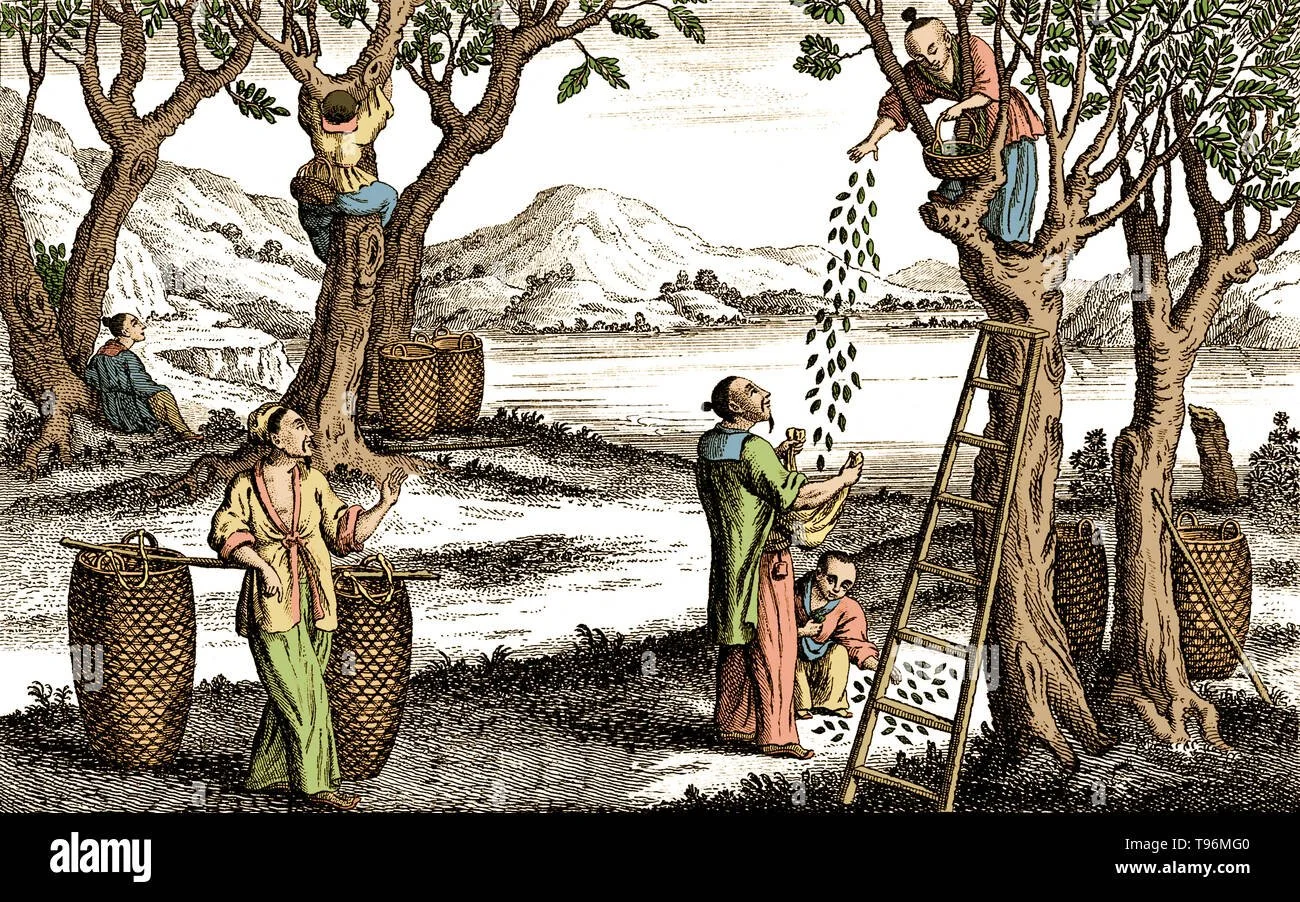

French authorities, drawing from successful sericulture in southern Europe, promoted mulberry plantations across their territories. In Louisiana, royal edicts from the 1730s onward encouraged the planting of white mulberry trees on colonial concessions, with some grants requiring planters to cultivate specific numbers—often dozens per acre—to support silkworm rearing. Agronomists envisioned vast filatures (silk-reeling workshops) along the Mississippi, exporting raw silk to Marseille markets and reducing reliance on Italian imports. Women and enslaved laborers played key roles, tending larvae in shaded sheds and reeling cocoons by hand—a labor-intensive process yielding threads of exceptional luster when fed on white mulberry leaves. Yet, challenges abounded: silkworms' fragility to humidity and disease, competition from indigo and tobacco, and the colony's instability thwarted large-scale success. By the 1750s, efforts waned, though small operations persisted into the early American period.

This broader context frames the mulberry stubs at Maison Chenal, which local historians and property records tie to one such experimental orchard. Established in the early 1700s on what was then a French Creole concession, the site likely served as a dedicated leaf farm for onsite or nearby silkworm farms. Harvested foliage would have been stripped daily during the trees' spring flush, fed to larvae in humid enclosures, and the resulting cocoons processed into thread for local weaving or export via New Orleans. The fruit—sweet but messy and short-lived—was a mere byproduct, perhaps sustaining workers or attracting birds, but irrelevant to the economic calculus. In an era without refrigeration or swift transport, mulberries couldn't reach distant markets viably; their role was purely foliar.

Maison Chenal: From Orchard to Architectural Oasis

Maison Chenal itself, a raised Creole cottage with bousillage walls and asymmetrical galleries, dates its core to before 1790, though its exterior evokes the 1820s. Originally perched beside False River, the structure faced demolition in the mid-20th century until rescued in 1975 by preservationists Pat and Jack Holden. The couple relocated it eleven miles to their newly acquired Bayou Chenal tract, envisioning a living museum of Louisiana's vernacular heritage. Over decades, they amassed outbuildings—like a 1750s pigeonnier, an 1829 barn, and the bousillage-clad LaCour House (c. 1760)—alongside 1,400 artifacts of Creole material culture.

The Holdens' vision extended to the grounds, recreating 19th-century parterres with heirloom roses and potagers enclosed by split-cypress pieux fences. Yet, the mulberry stubs—gnarled sentinels amid the clover fields—hint at the site's pre-plantation roots. As one local account notes, "In the early 1700s Maison Chenal was a Mulberry Orchard. Mulberry leaves were the preferred food for silk worms to produce silk." This aligns with regional patterns; nearby Georgia imported 500 white mulberries in 1733 for the same purpose, under James Oglethorpe's trustees. Though Louisiana's silk ventures never rivaled Europe's—yielding perhaps a few thousand pounds annually by the 1740s—the orchard at Chenal embodies the optimism of those schemes.

Legacy of Leaves: Why It Matters Today

Today, Maison Chenal operates as the Chenal Heritage Center for History, Culture, and the Arts, illuminating Louisiana's Acadian and Creole tapestry. Transferred in 2022 to Sam and Nori Lee, the new Stewards committed to preservation, the estate continues to host events amid its crawfish ponds and muscadine arbors. The white mulberry stubs, now ecological relics, shelter wildlife and evoke the invasive spread of Morus alba—a "trickster tree" that outcompetes natives but once promised prosperity.

This forgotten orchard underscores a poignant irony: colonial dreams of refinement, woven from fragile threads, dissolved into the subtropical haze. Yet, in their stubborn survival, these trees remind us of resilience—human, arboreal, and historical. As Louisiana grapples with its past, sites like Maison Chenal invite us to trace those threads, leaf by silken leaf, toward a richer understanding of the land's untold stories.

A Story of the Silk Echoes of Maison Chenal: A French King’s Vision and the Lives of Chinese Silk Masters in Louisiana

The Silk Echoes of Maison Chenal: A French King’s Vision and the Lives of Chinese Silk Masters in Louisiana

Nestled along the tranquil banks of Chenal Bayou, once the mighty Mississippi River, rest the majestic Maison Chenal. The Mississippi River changed course to form Chenal Bayou and False River, an oxbow lake, in the late 17th century. This occurred when the river, seeking a shorter path to the Gulf of Mexico, cut off a meander bend in what is now Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana, leaving behind the isolated body of water known as False River. Maison Chenal emerges like a whisper from the past. This 18th-century Creole cottage, originally part of a plantation owned by Julien de Lallande Poydras (April 3, 1740 – June 23, 1824) near the south end of False River, was relocated in 1973 to a 75-acre site graced with ancient white mulberry trees. Restored to museum-quality splendor by Dr. Jack and Pat Holden and now tenderly cared for by Sam and Nori Lee, the cottage radiates timeless elegance, housing a treasure trove of cultural artifacts.

Across its grounds, massive white mulberry trees—some six feet in diameter, meticulously aligned in rows—stand as silent sentinels of a forgotten ambition. The Holden family, who restored the site, recall that it cradled a white mulberry grove, likely planted in the 18th century under French rule. Intrigued by the grove’s meticulous arrangement and aware that mulberry fruit, soft and rich in sugars when ripe, spoils too quickly to have been a viable crop in the 18th century, the Lees turn their attention to the trees’ true purpose. Recognizing that white mulberry leaves (Morus alba), abundant in proteins, sugars, and amino acids, serve as the essential sustenance for silkworms (Bombyx mori)—a divine elixir for these silk-spinning creatures—they deduce the grove’s significance. The Lees interpret it as evidence of a royal experiment in sericulture, or silk cultivation, possibly commissioned by King Louis XV to bring Chinese silk expertise to Pointe Coupee. In the 18th century, Lyon, France’s silk capital, thrived as a global hub where mulberry groves fed silkworms and artisans wove lustrous fabrics for Europe’s elite, its connections to Chinese silk expertise via Jesuit missionaries and trade routes inspiring the king’s colonial vision. This dream, blending the hum of silkworms with the rustle of mulberry leaves, weaves a vivid tapestry of ambition and resilience, bridging East and West.

Pointe Coupee: A French Frontier Takes Shape

In the early 1700s, Pointe Coupee Parish blossomed as a vibrant outpost of French Louisiana, founded in 1699 by explorers like Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville. Its fertile lands along the Mississippi and False Rivers sustained indigo, tobacco, and rice plantations, worked by French and Acadian settlers and enslaved Africans. Under King Louis XV, the French crown viewed Louisiana as a strategic asset to counter British and Spanish rivals and enrich France with diverse exports. Silk, a luxurious fabric that adorned Europe’s elite and powered Lyon’s flourishing industry, became a tantalizing prospect. Lyon, transformed by royal edicts into a silk-weaving powerhouse, saw sprawling mulberry groves nourish silkworms and workshops produce intricate fabrics traded across continents, drawing inspiration from Chinese techniques. The white mulberry tree (Morus alba), whose leaves sustain silkworms, thrived in Louisiana’s warm, humid climate, making Pointe Coupee an ideal stage for sericulture, the art of silk cultivation.

Maison Chenal, a raised Creole cottage from the 1700s, stood at the heart of this vision after its relocation to the mulberry grove site. The Holden family’s oral history recounts that the site once hosted a mulberry grove, its massive trees—aged 150–200 years and aligned in orderly rows—now silent relics of a royal ambition. Likely planted in the 1730s or 1740s under French rule, these trees bear witness to their colonial roots. While mulberry fruit, cherished by Acadians as “murier” and Native Americans for its sweetness, spoiled too quickly for trade without refrigeration, the grove’s precise layout suggests sericulture—a bold attempt to cultivate silk for France’s glory, likely inspired by Lyon’s success and spurred by royal decree.

Louis XV’s Grand Colonial Vision

King Louis XV, reigning from 1715 to 1774, harbored grand ambitions for France’s empire. His colonies, stretching from the Caribbean to Canada, were meant to generate wealth, and Louisiana, though a financial burden, held untapped promise. Guided by advisors like the Duke of Orléans, Louis XV pursued economic diversification to reduce reliance on imports. Silk, a cornerstone of Lyon’s economy, was central to this strategy. By the 18th century, Lyon had solidified its status as Europe’s silk capital, its workshops employing thousands to produce shimmering fabrics for royalty and nobility, fueled by mulberry groves and Chinese-inspired techniques of silk cultivation. Lyon’s prominence was not merely industrial; it was a nexus of cultural exchange, connected to China through the Silk Road and Jesuit missionary networks. As early as 1684, Shen Fo-tsung, a Chinese scholar, arrived at the court of Louis XIV via Jesuit connections, followed by Arcade Huang in the early 1700s, who served as a translator and cultural intermediary. Though these were isolated cases of elite individuals, they demonstrated France’s fascination with Chinese knowledge. French Jesuits, active in the court of Emperor Kangxi, facilitated exchanges of goods and expertise, with gifts flowing between Kangxi and Louis XIV in the late 17th century. While Lyon lacked a settled Chinese community in the 18th century, its silk industry thrived on indirect access to Chinese techniques, likely inspiring Louis XV to recruit skilled Chinese artisans for Louisiana’s sericulture experiment.

To execute this vision, the king relied on the French East India Company, founded in 1664 to rival British trade in Asia. By the 1730s, its ships reached Canton, where Chinese silk dazzled European markets, deepening France’s desire for the expertise behind it. Through governors or Jesuit missionaries bridging East and West, Louis XV likely commissioned a small group of Chinese silk experts to bring their craft to Louisiana. Maison Chenal’s mulberry grove became a testing ground for a small-scale sericulture operation, reflecting the king’s ambition to emulate Lyon’s silk legacy in the New World.

The Daily Lives of Chinese Silk Masters

Around 1735, a group of four Chinese silk experts, their true names lost to history but imagined here as Li Wei, Mei Ling, Zhang Hao, and Chunhua, arrived in Pointe Coupee, carrying a 4,700-year legacy. Tasked by Louis XV, they transformed Maison Chenal’s mulberry grove into a silk haven. Sent by King Louis XV, these skilled artisans stepped into a world of swamps and opportunity, tasked with transforming Maison Chenal’s mulberry grove into a flourishing silk haven. Their names, evocative of their heritage, draw us into the lives they led, inviting us to connect with the vibrant legacy they wove in Louisiana’s frontier.

Li Wei, wiry and calloused from pruning, rose at dawn to tend the trees, using a bamboo knife to trim branches for their tenderest leaves, spacing trees 15 feet apart for optimal sunlight—a technique honed in China’s silk valleys. Mei Ling, his gentle companion, worked in a shaded shed, arranging silkworm trays with care. Her soft Yangtze lullabies soothed the larvae as she fed them fresh leaves, her touch almost maternal.

Zhang Hao, stout and discerning, oversaw cocoon selection, inspecting each silky pod with a craftsman’s eye. He patiently taught enslaved workers to identify the strongest cocoons, speaking in halting French. Chunhua, nimble and skilled, managed the reeling room, her bamboo tools unwinding threads from boiling cocoons as the scent of steamed silk filled the air. Their days followed a rhythm: mornings harvesting leaves, afternoons tending silkworms, evenings reeling threads under lantern light. Acadian cooks, inspired by rice and tea from Canton, blended Chinese flavors with Creole spices, enriching the plantation’s table.

Their presence wove a cultural tapestry. Acadian children, wide-eyed, watched Mei Ling’s silkworm trays, absorbing tales of emperors clad in silk. Enslaved workers adopted Zhang Hao’s knot-tying techniques, blending them with African patterns to craft distinctive cords. Chunhua shared tea and stories of Chinese festivals with Acadian women, sparking curiosity. The experts introduced bamboo, now flourishing across the 75 acres as a forest, used for silkworm racks and reeling tools, leaving a lasting mark on Pointe Coupee’s landscape. Their labor fostered a fleeting cultural exchange, bridging East and West in Louisiana’s wilderness.

A Dream Unraveled by Nature and Time

Despite the king’s vision and the experts’ skill, Maison Chenal’s silk cultivation venture faced relentless challenges. Louisiana’s humid climate, ideal for mulberry trees, bred mold and diseases like pebrine, decimating silkworm trays. Li Wei and his team struggled to maintain clean sheds, but the environment proved unforgiving. The labor-intensive craft—daily leaf harvests, constant tray tending, meticulous reeling—overwhelmed the small workforce of enslaved Africans that were unfamiliar with sericulture. While the French East India Company, weakened by wars and competition, offered scant support, leaving the project underfunded.

Economic realities further dimmed the dream. Indigo, sugar, and cotton promised faster profits, aligning with Louisiana’s plantation economy. By the 1750s, as France diverted resources to the Seven Years’ War, sericulture faded from royal focus. The 1763 transfer to Spanish rule halted French ambitions, leaving Maison Chenal’s grove to decline. A brief revival in the 1830s, during America’s “mulberry mania” with Morus multicaulis plantings, succumbed to disease and market pressures by the 1840s. The massive, now-dead mulberry trees stand as silent witnesses to this struggle.

Maison Chenal’s Shimmering Legacy

Today, Maison Chenal shines as a cultural beacon, its restored Creole cottage and grounds a window into Louisiana’s French past. The white mulberry grove, though lifeless, tells a story of bold ambition. The Lees’ insights, paired with the trees’ grandeur and orderly arrangement, suggest a sericulture operation, likely launched under Louis XV’s directive to emulate Lyon’s silk-weaving legacy. The lives of Li Wei, Mei Ling, Zhang Hao, and Chunhua—pruning trees, nurturing silkworms, reeling threads, and sharing traditions—paint a vivid picture of a dream that spanned oceans. Their techniques, from mulberry care to silk artistry, and their cultural contributions—songs, knots, tea—enriched Pointe Coupee, even if their silk never reached Lyon’s renowned looms.

Though the silk industry faltered, its legacy endures in Maison Chenal’s silent trunks. They stand as a testament to a king’s vision, a people’s skill, and a moment when Louisiana dared to spin silk under the stars. As visitors wander the grounds, they tread where East met West, where a delicate thread of ambition wove a fleeting, shimmering dream into the heart of French Louisiana.